As part of our mission to enhance discovery of and access to useful and relevant information resources for students and faculty, Milligan Libraries is pleased to now offer an embedded search interface on our website to Internet Archive’s Open Library project.

Started in 1996 with the mission to “provide Universal Access to All Knowledge,” Internet Archive is a non-profit digital repository of internet sites and other cultural artifacts, including books and texts, video, audio, software, and images. The Open Library project focuses on books and includes two primary components: an ambitious goal to build a universal online catalog of every book ever published, and providing a platform for searching and accessing millions of book holdings within Internet Archive. By linking to Open Library, Milligan Libraries instantly expands access to a vast array of book resources for our users.

Book holdings are added to Internet Archive through the digitization of print originals from library partner collections and donations. Book holdings include popular and academic titles on numerous subjects. Of particular interest, in addition to titles in the public domain (books whose copyright has expired and are freely available to the public), Internet Archive also digitizes and provides access to more recent titles that are still under copyright. (Internet Archive currently holds well over two million digitized books. Over one million of these have been published since 2000.) This access is made possible using a framework known as controlled digital lending (CDL).

For digital lending purposes operating within the legal limits of copyright fair use, CDL conceptualizes a digitized copy of a print book owned by Internet Archive (or its library partners) as if it were a physical print book. If Internet Archive owns one print copy of a book it can lend one digitized copy. While the digital copy is lent out the print copy is not circulated. Similarly, if Internet Archive owns 10 print copies of a book, it can lend up to 10 digital copies of that book at one time. Copy protection (known as Digital Rights Management, or DRM) is applied to the digital copies to prevent duplication and control borrowing by authorized users on the Open Library platform.

Getting Ready to Use Open Library

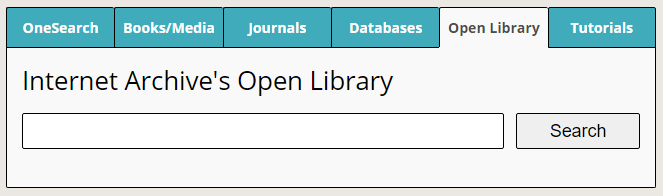

We have added an Open Library tab to the search box widget on the Milligan Libraries website homepage. (You can also select the “Internet Archive’s Open Library” link from the Resources > Specialized Resources A-L dropdown menu to go directly to Open Library.)

Before walking through a search session on Open Library there are a few setup steps to get out of the way first.

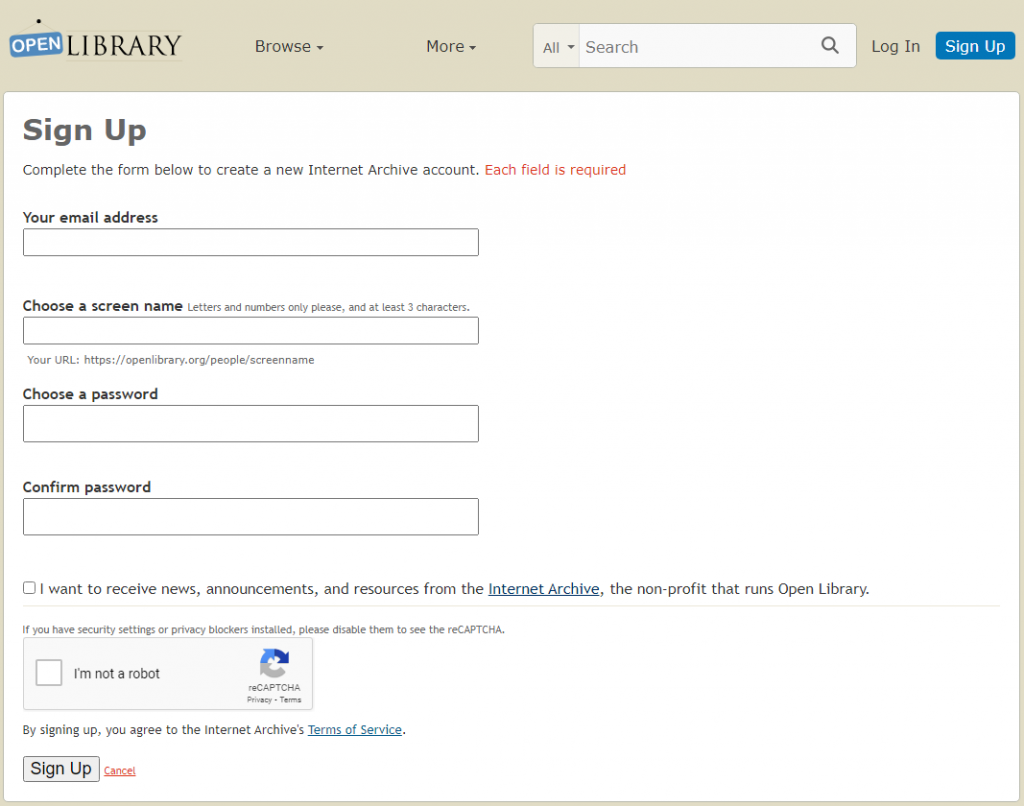

Step 1. Create a User Account. You can search the Open Library universal catalog and read public domain books using the online web browser viewer without creating a user account. However, a user account is required if you want to borrow CDL books through the online viewer, or download books to your computer or mobile device. Think of the user account as your Open Library library card. To create a user account, click on the “Sign Up” button at the top right of any Open Library page and fill out the form (click on screenshot to enlarge):

Step 2. Create an Adobe ID. As mentioned above, CDL book files (typically formatted as PDF or EPUB) on Open Library are copy protected to prevent duplication and control lending of copyrighted content. Internet Archive authenticates DRM-ed content using Adobe ID. Create an Adobe ID by signing-in here.

Step 3. Download Adobe Digital Editions and/or Bluefire Reader book reading software. You can bypass Step 2 and this step if you simply want to read books online using Internet Archive’s own web browser reader. However, dedicated software is required if you want to be able to download and read books offline. Books borrowed from Open Library are only readable on a computer or mobile device that supports Adobe ID authentication. Adobe Digital Editions (ADE) for Windows, Mac, Android, or iOS can be freely downloaded from here. An excellent alternative, Bluefire Reader for Android or iOS, can be freely downloaded from the Google Play Store or Apple App Store. ADE and Bluefire Reader are configurable to pre-authenticate with your Adobe ID.

Searching for Books on Open Library

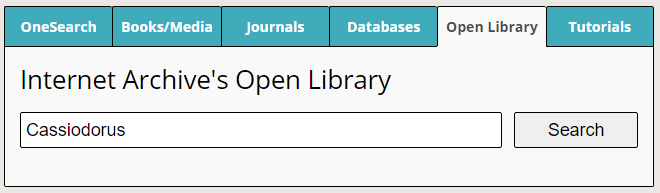

I have been doing some research on the sixth century Roman statesman and scholar Cassiodorus. I wonder what books by or about Cassiodorus might be available on Open Library. I type “Cassiodorus” in the Open Library search box on the Milligan Libraries website homepage.

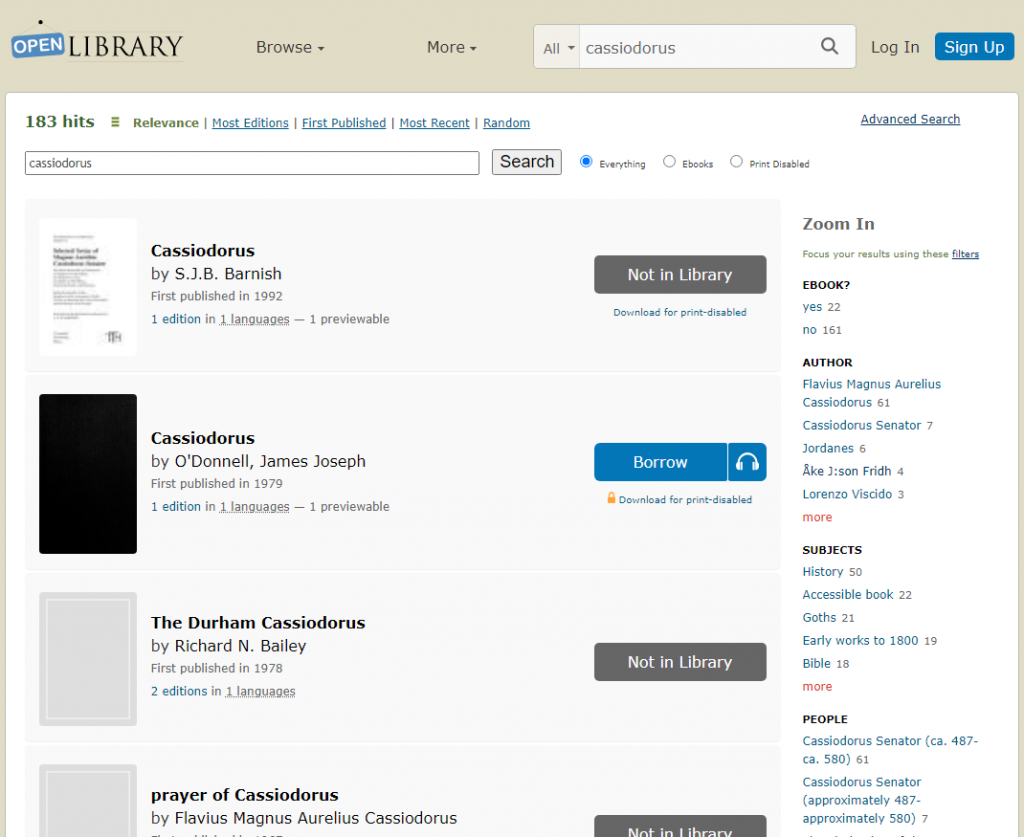

My search resolves to this results page (click on screenshot to enlarge):

At the top I see my search resulted in 183 hits. I also notice a list of facets in the far right column for ways to limit my search results in various ways (Author, Subjects, People, Times, etc.). To the right of each short result record I see large buttons variously labeled “Not in Library,” “Read,” and “Borrow.” The “Read” and “Borrow” buttons also have a headphone icon that slides over to enable a “Listen” (text to speech) option for print disabled users.

“Not in Library” indicates that a record has been created for this book as part of the universal online catalog, but a copy (or copies) of this book is not currently available on Open Library to be read or borrowed. Of interest, if I open this record, it includes a link to preview the contents of the book, and a link that pushes to the book record in Milligan Libraries’ WorldCat Discovery platform. These are very useful features. The book preview enables me to get a sense of the value of this title for my research, and pushing me into WorldCat sets up an option for me to initiate an interlibrary loan request.

“Read” indicates that the book is available on Open Library as a public domain title. Since copyright has expired on this title, absolutely no restrictions on access are imposed. The book can be freely read or downloaded without a user account.

“Borrow” indicates that at least one digital copy of the book is available on Open Library. But since this title is still under copyright, access is controlled under the controlled digital lending (CDL) framework described above. A user account is required to read or download the book. Incidentally, if all available copies of a book are currently borrowed the button changes to “Checked Out” or “Join Waitlist,” which gives me the opportunity to borrow the book once a copy is returned and made available again.

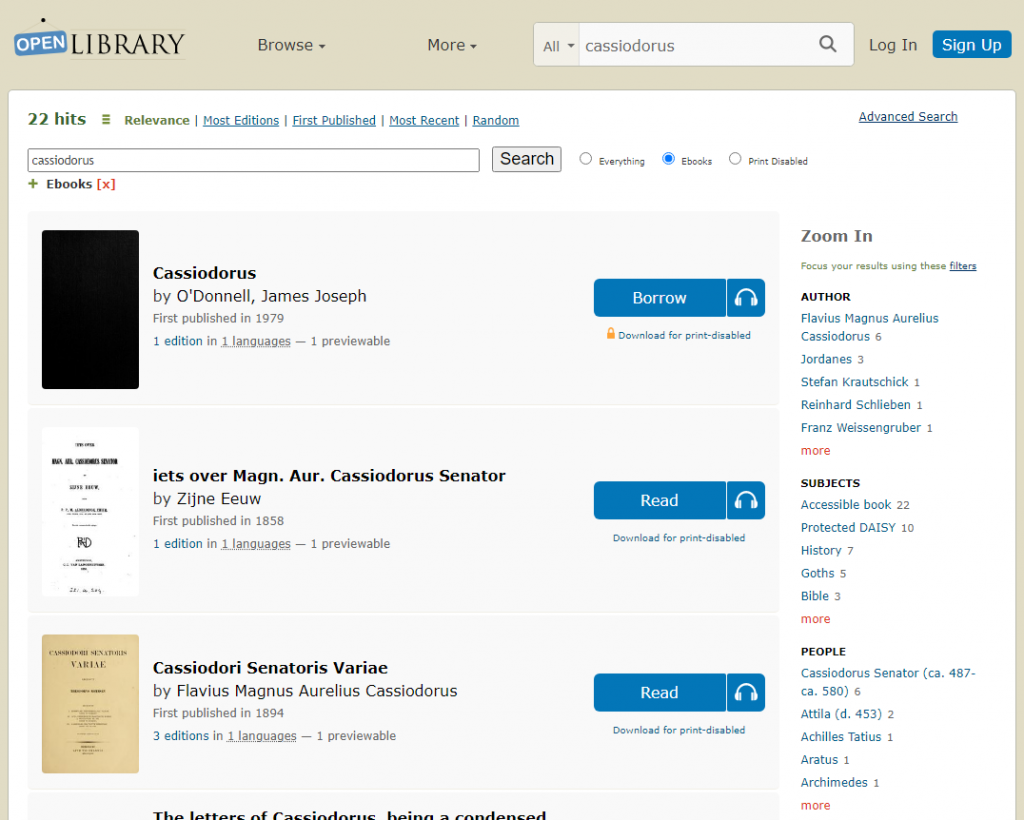

The default view shows “Everything” that resulted from my search (in this case 183 hits). However, if I click the “Ebooks” radio button at the right of the search box, Open Library only shows me a list of books that are actually available on the platform to be read or borrowed, as in this screenshot — 22 hits (click to enlarge):

Reading an Open Library Book Using the Online Web Browser Viewer

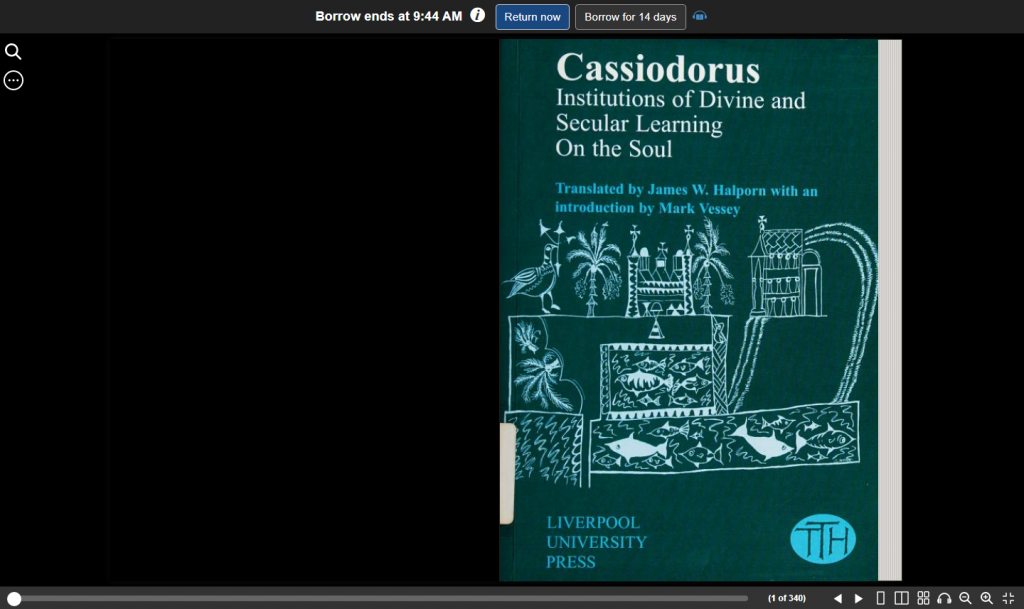

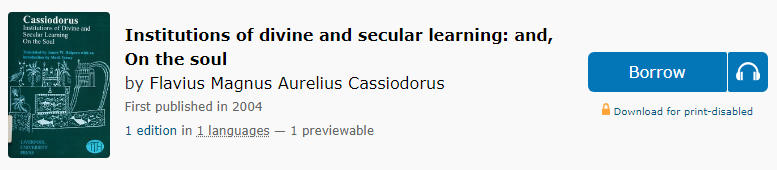

As I scroll down the list of books available to read or borrow on Open Library I see the title of a book written by Cassiodorus that I would like to read, Institutions of Divine and Secular Learning.

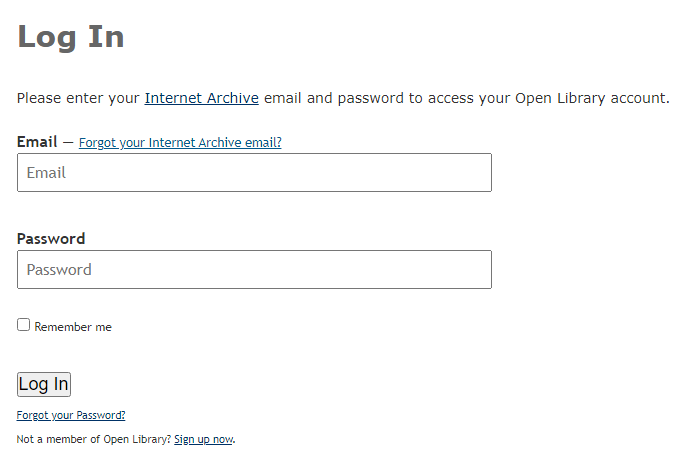

I click on the “Borrow” button. Since I am not currently signed-in with my Open Library user account I am prompted to enter my credentials:

Once I click the “Log In” button, the book is launched in Internet Archive’s online web browser viewer (click on screenshot to enlarge). An active internet connection is required in order to use the browser viewer for online reading:

I use the navigation slider or page turning arrows at the bottom of the screen to work my way through the book. Alternatively, I can choose a single page vertical scroll reading option. There is also a grid view for page picking, zoom in or out, full screen toggle, and text to speech audio reader.

The magnifying glass icon at the top left is for searching within the text of the book, and the ellipses icon (…) slides out to offer bookmarking, visual adjustments, sharing, and file download options (more on this in a moment).

The banner at the top of the viewer window indicates book borrowing options, and current borrowing status:

Borrowing options depend on the number of digital copies available for lending on Open Library. If there is just one copy available the book can be borrowed for only one hour at a time. (Note: As long as I continue reading, by page turns or scrolling, I do not have to return the book within the one-hour timeframe.) If Open Library has more than one available copy of a book I can borrow it for either one hour or for 14 days. Up to 10 books can be borrowed at a time. I can keep track of my book loans from my user account page. When I am done reading a borrowed book I can click the “Return now” button, which immediately frees my copy up for someone else to borrow, or I can simply let the loan period timeout on its own.

Download an Open Library Book for Offline Reading

Open Library allows downloading of public domain (“Read”) and available CDL (“Borrow”) digital books to my computer or mobile device (phone or tablet) for offline reading. As indicated in Getting Ready to Use Open Library, Steps 2 and 3 above, this capability requires the creation of an Adobe ID and the downloading and configuration of the appropriate reader software. These steps should be completed before attempting to download book files from Open Library.

I will demonstrate downloading and offline reading using the book I already have open in the online viewer above. I will be reading the book using Adobe Digital Editions. From the ellipses icon (…) I click on the “Downloadable files” option and select between an encrypted PDF or EPUB file. (PDF files retain original book pagination, while text in an EPUB file reflows depending on font size.)

I choose the PDF option, which downloads to my computer as a file labeled URLLink.acsm. You may need to browse or search on your computer or device to locate where downloaded files typically land. Look for a file with a .acsm extension. The advantage of pre-authorizing the reader software with an Adobe ID is readily apparent because launching the .acsm file will immediately launch the book in the reader:

I navigate through the book with single page vertical scrolling. I can adjust the text width or zoom for viewing comfort, and drop bookmarks. When I click on the “Library” button at the top left, Adobe Digital Editions opens a “bookshelf” view where I can see a list of my downloaded books, and time left on my loan. By right-clicking on any title in the “bookshelf” I can return the book or remove it from my library.

This tutorial is intended to help our users get started with Open Library as a remarkable resource for digital books. If we can provide you with specific assistance please do not hesitate to reach out.